As we embrace the festivities and traditions that come with Chinese New Year, it is essential to look back at the origins and evolution of this centuries-old festival—complete with mythical stories, astronomical calendars, and traditions that continue to influence how the holiday is celebrated today.

The Tale of Nian and the Birth of a Tradition

Chinese New Year is steeped in history, much of which intertwines with the story of Nian, a fearsome beast whose name coincidentally shares the same word for “year” in Chinese. As legend has it, Nian would terrorize villagers annually until a wise old man suggested using loud noises, firecrackers, and the color red to scare the monster away. This tale explains many of the New Year customs still observed: the hanging of red paper cutouts and the lighting of firecrackers to signal the “passing of Nian” and the celebration of new beginnings.

Lunar Calendar: The Moon’s Dance Dictates the Date

Unlike the Gregorian calendar, the Chinese New Year falls on a date dictated by the lunar calendar, specifically the second new moon after the winter solstice. This means that each year, the festival occurs on a different date in the period late January to February. This lunar-based system is not only unique to China but is also used by other Asian nations, such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, highlighting its significance and widespread cultural impact.

More than Religion: A Celestial Celebration of Spring

Predating both Buddhism and Daoism, the festivities are deeply rooted in an agrarian past and a celebration of spring akin to holidays like Easter or Passover in the Western world. The New Year tradition also coincided with the preparation for a new growing season, a critical time in an agricultural society.

Traditions and Customs: The Fabric of Festivity

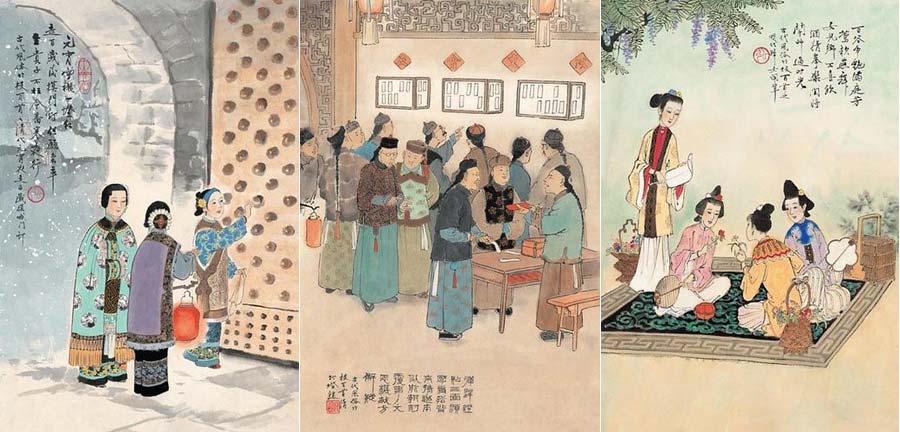

During Chinese New Year, also known as Spring Festival, families make it a priority to reunite—participating in what’s known as Chunyun, or the Spring movement, which sees one of the largest human migrations annually as people travel to celebrate with loved ones. The holiday traditionally spans 15 days, culminating in the Lantern Festival, marked by the lighting of lanterns and various local customs.

The customary “spring cleaning” is also a shared tradition, where homes are cleaned out to welcome the new year. It’s a time to clear away any bad luck and make space for incoming good fortune. From the lighting of firecrackers to the paper red lanterns swaying through the night, the holiday is rich in colorful traditions that captivate the senses.

Food: A Feast of Fortune

No Chinese New Year would be complete without its traditional fare. Delicacies such as nian gao, a sweet sticky rice cake, and savory dumplings are enjoyed, each with its own symbolic meaning, promising luck, wealth, and prosperity for the year ahead.

From Dynasty to Dynasty: The Evolution of Celebration

Tracing its origins back to the Shang Dynasty, when sacrifices were made in honor of gods and ancestors, the festival has seen considerable changes in customs and practices through various dynasties. From the Zhou Dynasty’s formalizing the term ‘Nian’ to the Han Dynasty’s setting the date of the festival, each era contributed to the rich tapestry of Chinese New Year traditions.

Modern Celebrations: Reinvention of an Age-Old Festival

Despite attempts to abandon the lunar calendar in 1912, the Chinese New Year—or the Spring Festival—prevailed, becoming an established public holiday after 1949 and a symbol of cultural heritage and continuity. The festival transitioned from religious roots to a social and entertaining occasion embraced by millions around the world.

Chinese New Year remains a vibrant and vital part of Chinese culture, embodying both the histories of ancient dynasties and the dynamic spirit of the modern era.

As expats or enthusiasts of cultural festivities, embracing Chinese New Year allows us to participate in a historical narrative over 3,500 years in the making. Let’s all welcome the new year with respect and enthusiasm, honoring an age-old tradition that continues to beat at the heart of Chinese society.